1. A Comparison

The way calculus is divided and presented varies significantly across universities and textbooks. In many curricula, calculus is split into two separate courses, commonly referred to as Calculus I and Calculus II. In such settings, Calculus I typically focuses on limits and differentiation, while Calculus II begins with integration, often introduced through Riemann sums, and continues with techniques of integration and applications.

At Middle East Technical University (METU), however, this division does not appear explicitly. Instead, the standard sequence consists of Calculus with Analytic Geometry followed by Multivariable Calculus. While these titles reflect the geometric and multidimensional aspects of the material, they can be somewhat vague in terms of content. For instance, topics such as infinite sequences and series are also covered within Multivariable Calculus, even though they are not inherently multivariable in nature.

For the purposes of this course, it is therefore useful to adopt a conceptual separation resembling the traditional Calculus I–Calculus II structure. In this framework, the present course will begin with Riemann sums and the theory of integration. This choice is motivated by two main reasons.

First, from a historical perspective, the notions of limits and differentiation emerged in the 17th century, largely driven by physical problems related to motion, change, and rates. These ideas were developed by Newton and Leibniz as mathematical tools to formalize physical intuition. Integration, on the other hand, acquired its rigorous foundation much later. The definition of the integral via Riemann sums, which interprets integration as the limit of an infinite sum, belongs to the 19th century and is closely associated with the work of Bernhard Riemann. From this viewpoint, it is natural to treat integration as a distinct conceptual development rather than merely the inverse of differentiation.

Second, the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus plays a central role in unifying differentiation and integration. It establishes a deep and nontrivial connection between two ideas that are, at first glance, conceptually different. Given its importance and its foundational role in the theory of integration, it is pedagogically reasonable to introduce integration as a new topic in its own right, rather than as a continuation of earlier material.

2. Bernhard Riemann

Figure 1: Bernhard Riemann (1826–1866), whose work laid the foundations of modern integration theory.

The modern understanding of integration is inseparable from the work of Bernhard Riemann (1826–1866), one of the most influential mathematicians of the 19th century. Riemann’s contributions span a wide range of areas, including complex analysis, differential geometry, and number theory, but his formulation of the integral remains one of his most enduring legacies.

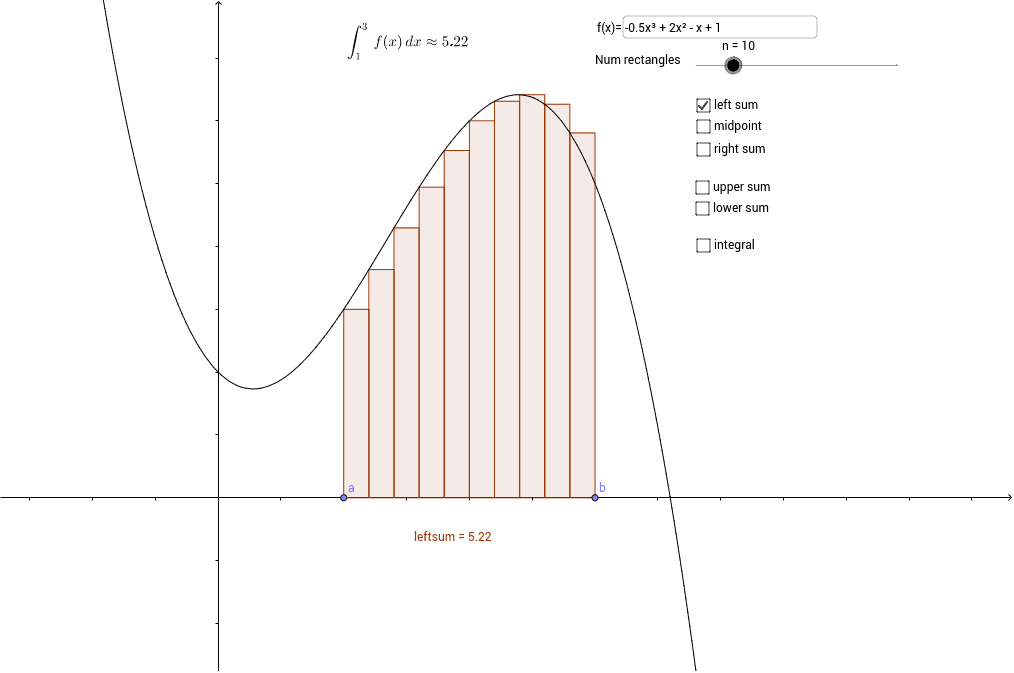

Riemann introduced a precise definition of the integral by approximating the area under a curve using finite sums over partitions of an interval. By refining these partitions and considering the limit of the corresponding sums, he provided a rigorous framework for integration that went beyond the intuitive geometric arguments used previously. This approach clarified which functions can be integrated and under what conditions, laying the groundwork for further developments in analysis.

Although later theories, most notably Lebesgue integration, extended and refined Riemann’s ideas, the Riemann integral remains fundamental in both theory and applications. It captures the essential geometric intuition behind integration and serves as a natural starting point for understanding more advanced integration theories. For this reason, Riemann’s perspective will guide much of our initial discussion of integrals in this course.

Figure 2: An illustration of a Riemann sum approximating the area under a curve.

Figure 2: An illustration of a Riemann sum approximating the area under a curve.

3. Main Topics to Be Discussed

- Integration

- Techniques of Integration

- Improper Integrals

- Applications of Integration

- Sequences, Series, and Power Series

- Partial Differentiation

- Applications of Partial Derivatives